Colleen McDonough surveyed the crowd assembling for the weekly Lunch in the Park program on the lawn of Philadelphia’s Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul… She spotted one man sitting by himself eating what might be his only meal of the day and she headed right to him with the most basic of questions: “How are you doing?” He smiled and said simply, ‘I’m good. You talked to me.’”

When I first read this in a recent Catholic-Philly article, I was struck by how simple but powerful Colleen’s words were. The man sitting by himself did not identify his free lunch as the reason he was doing well; rather, he pointed to the fact that another human spoke to him as the turning point in his day.

As a former Christ in the City missionary, I witnessed firsthand the power that human connection can have to transform someone’s life. I spent my two years of service, like Colleen, building friendships with people experiencing homelessness. I witnessed the full breadth of the human experience, watching my friends on the street struggle, despair, hope, fear, and occasionally recover. It was a privilege to look with the eyes of Christ on people who are so often overlooked in modern society. It has been a year and a half since I left full time ministry, and I have learned a lot since then about the ways that contemporary life is inconducive to human connection. One of the primary ways I see human connection threatened is the prevalence of transactionality in our lives.

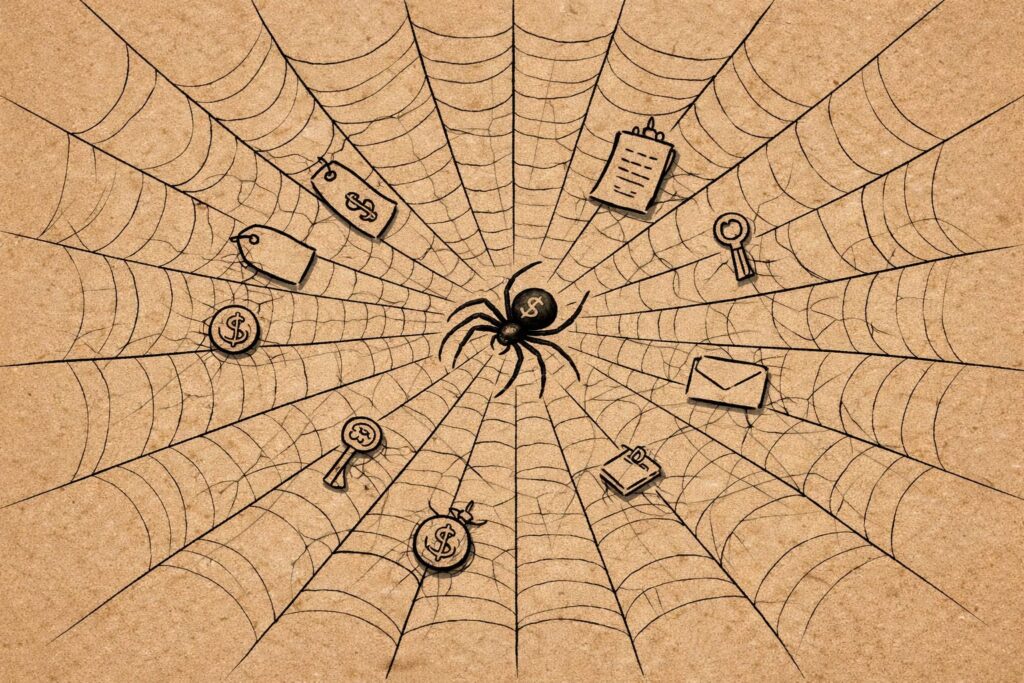

Transactionality infects a shocking amount of contemporary life, quietly weaving itself into places we rarely question. The easiest place to identify transactionality is in our economic exchanges with others. We pay people to drive us to our hotels, to clean our houses, to cook our meals, and even to care for our young children or elderly parents. The modern workplace is almost entirely transactional: you provide labor to your employer, your employer pays you for your work. And, of course, exchanging money for goods and services is a necessary and often good activity. However, it becomes a problem when the act of transaction extends beyond our economic needs and affects how we view each other as human persons. A spirit of transaction fundamentally keeps people caught at a safe distance from each other, entangled in threads of isolation. When transactionality colors our interactions, it results in alienation because we start to use each other as tools rather than see each other as persons.

An example of how transactionality can be alienating is in the use of ride-share apps, like Uber. When you get in the car with your Uber driver, your relationship with that person ends as soon as he drops you off (assuming your payment went through). You have no further responsibilities or concerns regarding your driver; any demands on your time resulting from your brief interaction have been neatly settled, and you can go your separate ways. Now, the existence of rideshare drivers isn’t necessarily a bad thing (I myself have been very grateful for a quick pick up in a pinch). However, an Uber ride is an encounter between two persons that is utterly alienated; you have no further relationship with your driver than before you got in his car. Your interaction was completely transactional.

Transactionality is so commonplace that it even weaves its way into our interactions of serving the poor. While material compensation is seldom the primary motivating factor for homeless outreach, it can be tempting for good-natured people to see the homeless as problems to be solved, rather than people to be served. A volunteer could serve food to the homeless to assuage their guilt for their own possessions, or, even more callously, as a way to check off the box for their company service hour requirement. Transactionality here cuts against the whole point of homeless outreach, which is to treat those experiencing homelessness according to their dignity as a child of God. Instead, it reduces them yet again to something less than they are: persons to be loved.

Conversely, the homeless woman, in the overwhelming pain of her hunger, might easily begin to see people in her life as nothing more than access points to the resources she desperately needs. Perhaps unknowingly to her, all her relationships become transactional. She is trapped in the web of transactionality, not able to look beyond an empty hand extended in solidarity to the friendly eyes of the person offering it. This alienation contributes more and more to her suffering, driving her deeper into the isolation known as the “poverty of loneliness”. Material poverty is often the symptom of this isolation, not its source. If this weren’t the case, transactionality would be enough to solve homelessness, but the need for healthy relationships is not solved by a simple exchange of goods.

Resisting the cultural pattern of transactionality touches the core of our ministry. We must seek to know her as a person for the sake of friendship first. Of course, our hope is to help her get off the streets, because what friend wouldn’t? But offering the homeless woman something even more essential than a housing voucher: a relationship free of transaction will bear more lasting fruit. An encounter with the love of Christ is what her soul desperately needs. This gift, the gift of Christ’s love, is ultimately the deepest and most fitting response to the “poverty of loneliness”, which could never be filled by a government housing program or a packaged lunch.

At Christ in the City, missionaries seek to break the pattern of transactionality and change the culture of mutual use to mutual encounter, one human interaction at a time. How can you reach out to others in a way that breaks through the ties of transaction to build a habit of human connection?

A guest post by Olivia Prevost